Interpreting Slavery In the Trump Era

ARE TIMES CHANGING?

The morning after Donald Trump was elected president, African American museum interpreter Anterior Leverett was feeling depressed and frustrated. But she forged ahead to work. She was scheduled to give a school tour about the Civil War to 11th graders. She tried to center herself with the thought that this was an older group, so there might be opportunity for some good discussion around race and the contemporary connections to a war fought over slavery.

Atlanta History Center's Civil War exhibition "Turning Point," where Anterior Leverett gave a tour on the morning of November 9th. (Photo: Atlanta History Center)

But once engaged in the tour (which includes a role-playing simulation where students represent soldiers) the mood of the students took a different turn.

Spontaneously one student started chanting “Trump! Trump! Trump!” Soon the whole class had broken into a Trump chorus right there in the exhibition.

Anterior Leverett, a trained actor, is a museum interpreter at the Atlanta History Center

“I was stunned because I knew that these white kids were old enough to understand the implications of chanting 'Trump' at that moment. We were discussing the enslaved perspective of the war. It was like they wanted to get a reaction out of me. I just tried to quiet them down and go on.”

Maybe it was the subject matter of the Civil War, or being swept up in the thrill of playing the role of a Confederate soldier, that inspired this student to loudly celebrate a presidential candidate who has been celebrated by white supremacists. We can't be sure what caused the outburst and subsequent chanting. But at that moment, Anterior felt the weight of both historic and current-day racial tension.

As history educators, we strive to make history relevant (the buzz word of the day, right?). If we’re doing our job right, we make those connections between the past and the present. For this group, connections were made -- just not the way we intended. I created the Civil War tour that Anterior gave that day (called “The Price of Freedom”) in 2011. Along with the main goal of building critical thinking skills through decision-making, it was also designed to elicit emotion – emotion about the stakes of the war and the costs to many different kinds of Americans. I wanted students to be personally connected to the stories of individuals from different backgrounds. But when you elicit emotion, it comes with the risk of unpredictable moments. Many of those moments are poignant and revelatory - when students show strength of character or empathy. But some are like the one described by Anterior.

Are times changing? Will we have more and more of these kind of emboldened and racially charged comments in our museum galleries? And if so, should we change the content or structure of interpretation that deals with racially sensitive issues and especially slavery?

Addae Moon - Director of Museum Theatre at the Atlanta History Center (shown here speaking at the Ibsen Theatre Conference in Norway)

Listen to my conversation with Addae Moon (Director of Museum Theatre, Atlanta History Center) as he gives his take on how today’s visitor may be different and what museums must do to respond:

Will telling stories that dig deeply into racial issues be seen as increasingly “radical?” Addae gave me a lot to think about. He always has, ever since our offices were next door to each other at the AHC. Everyone needs a colleague like him who pushes you to expand your thinking on a daily basis.

PLAYING THE PART: SLAVERY AND LIVING HISTORY

When museums interpret the institution of slavery through living history, there’s always a chance things will go sideways. People bring their preconceived notions with them to a museum or historic site, and it is up to our interpreters/educators to negotiate the landmines. But let’s not forget that the real world is presenting some very real challenges for our front-line staff too, especially for those of color.

It was always hard to play a slave, but today it may be even harder.

Shannon Little (on the right) plays the role of "Cuffy," a young enslaved woman in a scripted outdoor play put on by Accokeek Foundation in 2014.

Here, I speak to Shannon Little, a former living history interpreter who was on my staff at Accokeek Foundation. She explains, with great insight, why she quit her job in the summer of 2015.

I’m grateful for Shannon’s story and her honesty. It is an important reminder that now is a good time for museums and historic sites to re-examine the way they approach race and slavery. What stories should we tell? How should we tell them? And how can we best support our front-line staff facing new challenges?

Given her experience, I asked Shannon if she thought that museums should back away from interpreting slavery through living history. Maybe it’s a traumatic set of narratives that is just too hard for interpreters and visitors to deal with in this realistic way right now. She said it was a tough call. “It’s a lot to ask of someone to play that part,” she said.

Some African Americans tire of dwelling on this often revisited part of history, regardless of the method used. C. Hub Magazine just published a thought-provoking piece by Faustina Anyanwu called “Black People Must Reject Slavery as Their History in 2017.” The author isn’t suggesting that we omit slavery from American history, just that focusing on it so heavily can contribute to negative self-images for African Americans. She advocates mixing in more stories of resilience and instilling pride in black accomplishments, rather than focusing on helplessness.

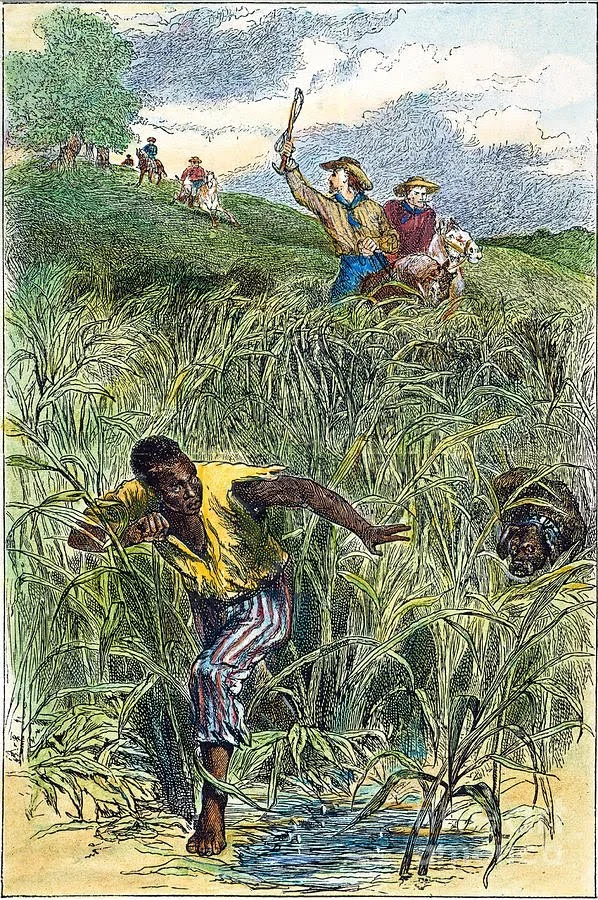

Addae Moon: Stories illustrating the agency of slaves should be mixed in with those of hopelessness. (Illustration: New York Public Libary, artist unknown.)

Addae Moon agrees that dwelling only on traumatic stories, can be too much sometimes. But he says we can’t shy away from the negative side of slavery.

“There are a lot of white folks out there who need to see the harsh reality, but we can and should mix in stories that show the agency of enslaved people. How they survived in spite of those conditions.”

Addae made me think about who our visitors are and whether the narratives they NEED to hear right now may be different. I’ve heard enough un-enlightened comments about slavery from white visitors over my career to make me want to continue to shine a light on the worst parts of slavery. No, slaves weren’t just a part of the family, as many have told me. And I think living history and museum theatre are powerful tools for humanizing the truth. On the other hand, I think there is something important about what Shannon related about the triggering affects of slavery portrayed realistically for African American visitors who are seeing discrimination play out in their current-day lives.

We can help visitors by being clear about the content of programs and exhibitions and by giving support to our interpreters. In my experience, interpreters who are ultimately successful at playing enslaved characters find inner motivation and purpose in doing the job.

Here is Shemika Berry, a living history interpreter explaining why portraying enslaved woman, “Cate Sharper,” on the National Colonial Farm (run by Accokeek Foundation) is important to her, especially now.

Shemika Berry works as a museum interpreter for Accokeek Foundation, but also has her own business portraying other historic black women for school audiences.

Shemika has found her own motivation for performing the role of an enslaved woman, but institutions can also take the lead in fleshing out the underlying purpose and direction for the interpretation, which ultimately gives interpreters the help they may need to find the larger purpose in portraying a slave - or slave holder, for that matter.

HOW CAN WE BEST SUPPORT OUR

FRONT-LINE EDUCATORS AND INTERPRETERS?

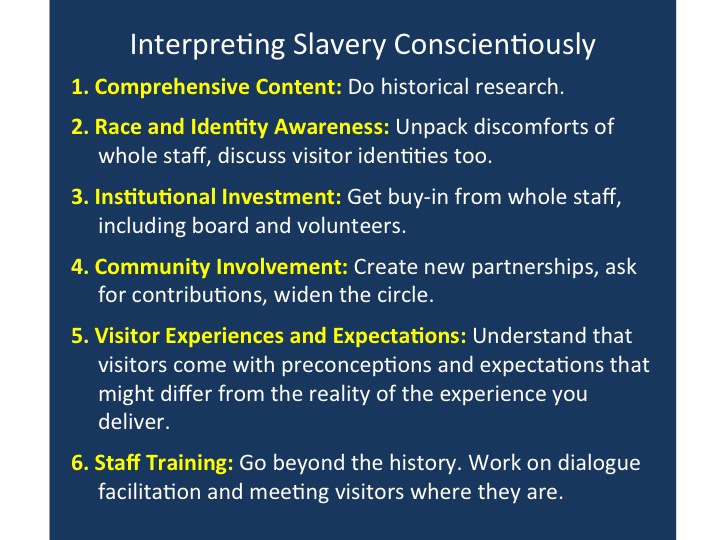

According to Kristin Gallas, co-editor of Interpreting Slavery at Museums and Historic Sites, it’s an effort that should involve not only interpreters, but every single person in the organization. She offers 6 steps or actions that can help museums offer “comprehensive and conscientious interpretation of slavery.”

From "Developing a Comprehensive and Conscientious Interpretation of Slavery at Historic Sites and Museums" by Kristin Gallas and James DeWolf Perry (Interpreting African American History and Culture at Museums and Historic Sites, edited by Max VanBalgooy)

I can’t agree more with Kristin that the process of having purposeful and thoughtful slavery interpretation ought to involve the whole staff. Unpack those skeletons. Having the hard discussions about race, from the Executive Director to the custodians, will make for a healthier organization. Through her work with the Tracing Center and independently, Kristin has helped organizations through this process. Check out her book (co-edited with James DeWolf Perry) on Interpreting Slavery and her forthcoming book, Interpreting Slavery with Children and Teens.

But what if your museum is small and you can’t afford the time to engage in this kind of comprehensive soul-searching, research, and training? Kristin addresses this here:

Kristin and I agree that the museum field needs to place more value on our front-line education staff.

“To be an educator should not be a $10/hour job. This is my new crusade,” she said passionately.

She described two institutions, one very large and one small. Both had invested significant resources researching the history of slavery for their sites. The larger one invested thousands of dollars in a cutting edge exhibit about slavery. The smaller site had even changed their name to include the words “and slave quarters.” They were making strides to be genuinely inclusive. But in each case, Kristin recalled experiencing sub-par guided tours that glossed over deep issues and showed little sensitivity. The experience is “only as good as your docent,” she said. This is painful for me to hear. We have a real opportunity here to have some meaningful discussions, but not enough attention is being paid to training interpreters to conduct dialogues. Truthfully, it’s easy to learn the historical content of the tour. The more important skill we need to cultivate is the engagement techniques, including dialogue.

When I asked Addae how Atlanta History Center interpreters were handling their feelings related to racial tension in the last year, he explained that the group has regular discussions about what’s happening on the floor. They’ve also received dialogue training from Sites of Conscience. And judging from my talk with Anterior Leverett, they feel supported by the management staff.

Regular training about how to deal with difficult situations is something embraced by the Atlanta History Center and the Tenement Museum, and I hope other museums also are considering prioritizing interpreter training. I’m with Kristin. We’ve got to invest in these guys. They are the key to deeper engagement and addressing, with nuance, racial tensions that inevitably enter the museum each day. I'm just not sure we're going get the results we want with a corps of volunteer docents or even part-time educators, unless everyone is committed to the training.

On a side note about designing interpretive programs (which could be a whole other blog post), I recommend providing more of a structured framework when dealing with sensitive issues, when possible. This means meaningful introductions, opportunities for dialogue at the end, and some scripted parts for interpreters – even at living history sites. With more structure, there is more safety for the interpreters and the visitors to go to deeper places.

So will the Trump Era scare museums into recoiling from interpreting slavery in meaningful ways? Will we go backwards?

Here is what Kristin Gallas has to say about the museum field’s trajectory

Like Kristin, I’m encouraged by what I’ve been seeing in our field. Every conference I attend contains packed sessions on interpreting difficult history, social justice, and being more inclusive in hiring. Let’s continue our progress. And if you need further inspiration to continue this important work in the face of heightened tensions, here is Christy Coleman, CEO of the American Civil War Museum , long-time advocate for robust and dynamic interpretation of slavery, and truth-teller.

(The whole program is great, but long. If short on time, listen from 14 minute mark– 18 minute mark )

To contact Kristin Gallas: kristin@interpretingslavery.com

For more posts like these, subscribe to Peak Experience Lab blog (below).

Contact Andrea at andreajonesmail@gmail.com to create your own peak experiences.