Behind the Curtain: How to Build a Meaningful Museum Experience

[8-10 minute read]

The word EXPERIENCE is gloriously overused in the museum field. To clarify, I’m not talking about the ease with which a visitor navigates a website or finds the museum bathroom (although both of these are important). I’m talking about meaningful, in-person experiences that inspire visitors to feel something -- wonder, togetherness, purpose. I’ve written about why we need more of these in museums, but how do you make them?

Using an AASLH Conference Session to experiment and collaborate

I have an experience design process that I use and I conduct workshops to teach it to others. But I wanted to find out how other people design. How do they make the magic happen? I reached out to some of my museum experience heroes – the Indiana Historical Society and Second Story Studios.

The idea was to use the AASLH conference session as a vehicle to work together to create an experience from scratch instead of showcasing past projects. This way we could learn from each other and hopefully create something fresh and interesting for conference-goers. It turned out to be my favorite design experience of the year!

Cue “Eye of the Tiger” entrance music:

STEP ONE

Compare Notes: What ARE the elements of a meaningful museum experience?

If we were going to teach others how to design meaningful experiences, we had to agree on what we were shooting for – like a rubric. Over the years I’ve come up with four core ingredients or tenets for what I call a Peak Experience (hence the name of my business). When an experience is not quite having the impact I was hoping for, it’s usually because one of these tenets is missing or needs improvement.

Here are my 4 tenets along with the rubrics used by my teammates. Lots of interesting similarities and differences:

Creating a rubric for meaningful experiences is an extremely worthwhile exercise. Museum people often talk about learning goals, but what do we want our visitors to experience? If you can distill your experience design priorities then you can replicate the wizardry again and again. You’ve also got a tool for analysis when audiences don’t respond as you had hoped.

STEP TWO

Agree on Topic: What’s it about?

The conference took place in Austin. One of Second Story's tenets was for the experience to be “site specific.” And AASLH is a history conference. So we started researching Austin history. No biggie, just all of Austin’s history. But this is how lots of projects start, right? With a big hairball of content. The skill is in how you untangle it.

We went in search of stories that seemed interesting and felt distinctly “Austin.” The story we landed on was the poisoning of a famous tree in downtown Austin called the Treaty Oak.

I won’t go into all the details (although the tale is utterly fascinating). But the basics of the story are this:

We were all attracted to this story because, as outsiders, it all seemed so bizarre. The crime itself was strange. The extreme reaction of the locals (and even the world) seemed over-the-top. Yes, it was an iconic tree, but that’s quite a lot of effort and money to invest in saving it. What did this tree symbolize to the those who fought to save it – a changing Austin needing to preserve the last emblems of tradition? The momentum of a burgeoning environmental movement?

A thought-provoking experience is always built upon a story that is about more than the occurrence itself. It must be a story that hits at a deeper more universal level.

A more trivial treatment of this story could have taken on a “who dunnit?” murder mystery focus – not homicide, but herbicide! Sort of fun, sure, but what is this story really about? How can we help people learn something about themselves? (Peak Experience tenet: make it thought provoking)

We decided to focus on the idea of tradition vs. progress. It seemed relevant to today, given both our current political struggles and the removal of Confederate monuments. I like the odd pairing of the tree-hugger (usually progressives) with the idea of maintaining tradition. Aren’t progressives usually in favor of embracing change? It was unfortunate that the this happened to the tree, but when is it time to move on? This got me thinking – this idea of when to move on – it applies to so many stories in our lives. We’ve got something good here.

We decided to frame the experience around this essential question:

STEP THREE

Zoom in: What moment in our story helps audiences answer the essential question?

Too often, museum exhibits and programs attempt to tell the whole story of a historic event -- or of a decade, or even of a century. But it’s the individual moments that are really memorable. It’s in the vivid detail that we get attached to characters and feel emotion – not within the pages of an encyclopedia. All three of us agreed that one of the most important elements of experience design is to NOT overwhelm audiences with too much content.

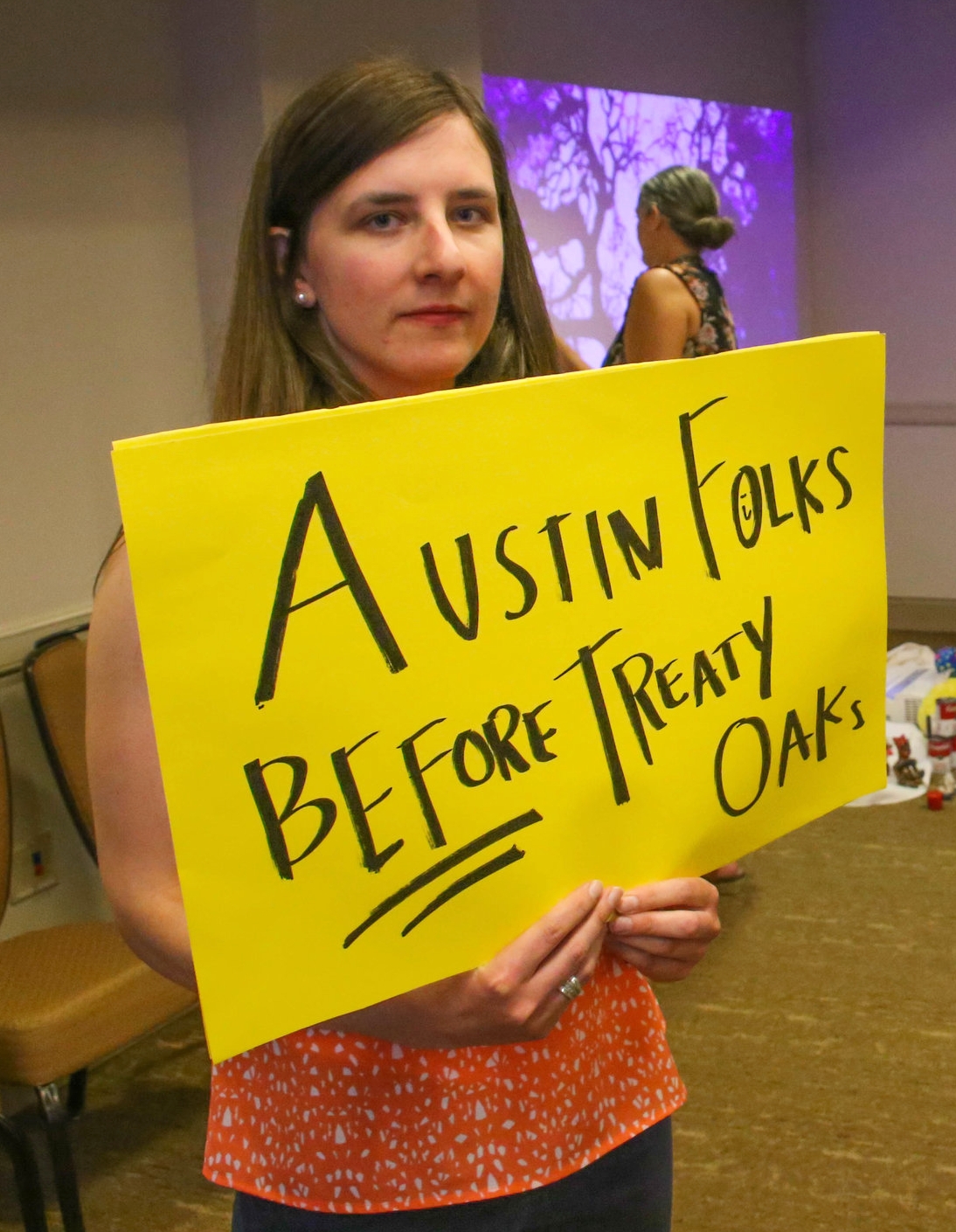

After reading the story above about Treaty Oak, which moment would you have brought to life? We initially thought about zooming into the crime itself - the actual poisoning of the tree by Paul Cullen. This dramatic act would be surprising and novel. But we wanted the audience to get swept up in the grief of losing the tree, just like the locals in 1989. We also wanted them to wonder if saving the tree was the right thing to do. There were, after all, a small minority of folks within Austin that felt that saving the tree was a waste of time and money.

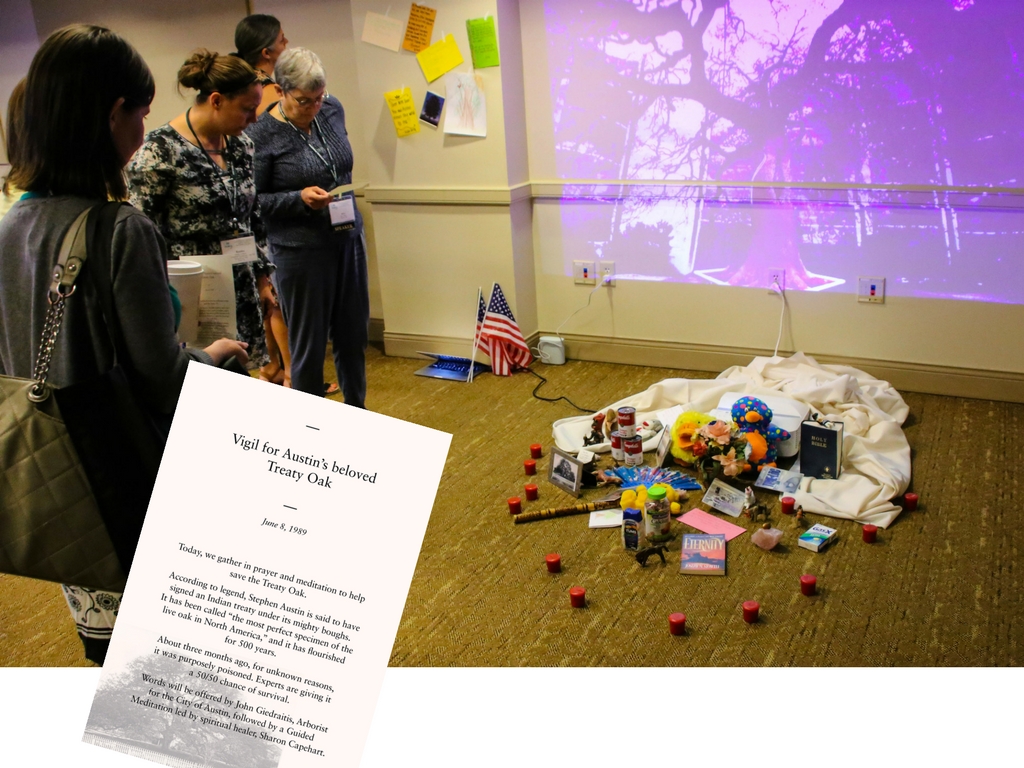

Ultimately, we decided to recreate a specific Treaty Oak vigil that occurred on June 8, 1989. The moment had all the elements we needed, plus the added “Weird Austin” element of a psychic led spiritual healing of the tree!

At this moment in history, at the vigil, Austinites didn’t know if the tree would survive. They also didn’t know exactly who poisoned it. If the audience walked into the story at this moment, they could feel the gravity of the loss. But there would be plenty of unanswered questions that would leave them wanting more information.

In our group’s discussion, we agreed that leaving out information may be a higher art form than putting it in. Always leave them hungry for more, not fatigued and out of questions.

STEP FOUR

Design the experience: What tools should we use?

After picking our historic moment, the hardest part of the design was picking the right tools. Would this be a self-guided or facilitated experience? Would we use technology? How would people participate?

Our group discussed the all-too-common pitfall that museums often fall into – picking the tool before designing the experience. How many grant applications has IMLS received that ask for money for “a new mobile app” without specifying why this is the tool for job. Or without fleshing out what the “job” really is? "Experience before form" is one of Second Story’s key tenets and I completely agree.

In designing our Treaty Oak Experience, we knew we wanted to involve our audience in the vigil. We wanted them to feel a part of something together, to create a memory, and to be swept up in the moment. We just need to figure out the form factor.

Just like in a real museum project, we had to grapple with creative constraints – the reality of our circumstances. During our session, we emphasized that a good experience is built on the specifics of your circumstance. We were dealing with a 75-minute time constraint, an ugly conference room that could not be altered, a couple of months to build it, and no budget.

Because we couldn’t alter the environment that much, we knew that the magic had to be produced in the audience’s imagination. This is why we ended up using a tool that Dan and I were very familiar with – theatre. Theatre is a great tool to use when you’re working with a defined time period and you need maximum impact. Through some friendly contacts we recruited 3 great actors.

Since this was going to be immersive theater, audience members played parts too - local Austin vigil attendees.

The only real set piece was a projection of the tree onto the conference room wall and an altar of “get well” items on the floor – cards, letters, chicken soup, candles, and medicines.

(The real items from the Treaty Oak altar have been preserved and archived at the Austin History Center)

Step Five: Showtime!

As people walked into the room (into what they thought was a normal conference session), we handed out a small vigil flyers – a clue that they had just time traveled - and welcomed them to the 1989. The actors, in character, circulated around the room and encouraged people to pay their respects to the tree and visit the altar.

Each person was given an acorn and invited to ”vote” their worldview. This element of the experience was designed to prime the participants’ minds to think bigger and deeper about what they were seeing - and to scaffold their thinking for the essential question, which we would ask during the debrief.

Participants were also encouraged to connect this Austin event to other threatened landmarks that are important to them.

Merlin Bell (Missouri History Museum) – playing City Forester John Giedraitis

The self-guided portion of the experience ended and the “show” portion started as the character John Giedraitis (city forester) sang “This Land is Your Land” and gathered everyone around the tree. In real life, there is no evidence that John sang at the vigil, but we wanted a cue that was better than

“Hey come over here!”

Ellen Kuhn (Missouri History Museum) – playing a protester

John then gives a monologue about the tree’s meaning to him (he proposed to his wife there) and what his staff has been doing to try to save the tree. With his passion, he garners rousing support from the tree-loving crowd.

Just as enthusiasm is building, John is interrupted by a protester who is outraged that so much attention is being given to a tree when there are people, homeless people, that need help.

The addition of the protester in the design was very purposeful. There was no protest at the real vigil. But there were newspaper editorials voicing these opposing viewpoints. There were also Native American leaders who welcomed the death of a tree that represented a loss of land and tradition. One of my tenets of experience design is to include multiple perspectives in any experience. We made the decision to not adhere to a literal version of this event so that we could present a more complex and nuanced story.

Stephanie Kent (a grad student at University of Texas) – playing psychic healer Sharon Capehart

John then explains that although he is a man of science, it never hurts to try unconventional methods of healing. He invites psychic Sharon Capehart to the front. Sharon leads the group in what she calls an “energy transfer” – bad juju out, good juju in!

Two audience members are asked to touch the tree (projection) and the rest of the audience is invited to touch the shoulder of someone who is touching the tree. A chain of love!

This meditative music plays (to help the audience get into the moment). If you'd like to imagine what it felt like in the room, press PLAY:

The audience summons a room full of good energy for the tree and are then instructed to release the bad energy into the atmosphere. Release!

And the energy transfer is complete.

John thanks everyone for coming, offers a few more hopeful words for the tree, and the vigil is over.

Then, the most important part of a participatory experience like this: everyone comes out of character for the debrief. We led a discussion with participants about what they saw and questions they had.

The first thing they wanted to know was who tried to kill the tree and if it survived. They were hungry for information about this event and about the history of the tree. Exactly what we had hoped! We had successfully inspired curiosity instead of overwhelming the audience with information. This is why I like front load with experience, then reveal background information.

We also discussed the idea of tradition vs. progress and when to let go of the past. One woman (who was actually from Austin) said she was surprised how attached she was to the tree despite identifying as a progressive. Those not from Austin seemed to have much less sympathy for the tree. We discussed how local landmarks contribute to our sense of belonging to a place.

We then moved to a discussion on design. These savvy museum professionals wondered how you would put this exact experience in a museum. What if you don't have access to actors or any staff at all.

Laura and I were brimming with ideas about this exact proposition. How would you do it?

But yes, this experience was designed for a conference session not a museum – because you should always design for the actual circumstance. But more than the specifics, we were attempting to connect people with the feeling of being part of something special for a brief moment in time. And to get a roomful of museum minds hooked on recreating that feeling in their own museums and in their own ways.

Andrea Jones is a consultant specializing in helping museums to create transformative learning experiences. She conducts workshops, designs experiential programs and exhibits, and assists museums in untangling their "content hairballs."